The Reformation of Worship

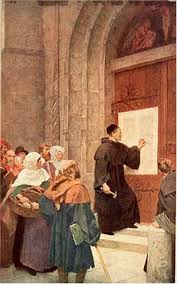

October 31, 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther nailing the “95 Theses” to the door of the church in Wittenberg — a signal event often viewed as launching the Protestant Reformation. Many churches will be commemorating and celebrating this anniversary, but this strikes some as odd. A Roman Catholic friend once asked me how it was that Protestants could celebrate one of the greatest schisms in the history of the Church. I replied that we don’t celebrate separation. The Reformation was a tragic necessity given the condition of the Church at the time. We celebrate the fact that the Reformation was a time of recovery and renewal in doctrine and practice. Nowhere is this more evident than in the matter of worship.

The words of a modern Roman Catholic can help us understand the necessity of the reformation of worship in Luther’s day. Josef A. Jungmann, one of the leading Roman Catholic liturgical scholars of the 20th century, outlined the state of late medieval European piety in a 1959 journal article entitled, “Liturgy on the Eve of the Reformation.” While noting some external signs of vibrant liturgical life (active participation in events of church calendar, multiplication of gothic cathedrals, etc.), he acknowledged many signs of weakness and decline.

One key problem was the shift from worship by the people to worship by and for the clergy: “the liturgy was a liturgy for the clergy … [even] in the churches in which the worship of the faithful should have been the primary concern.” Literal barriers entered the sanctuary, such as the rood screen behind which the clergy conducted the mass. Then there was the language barrier, with the services conducted in Latin that the people could not understand. Jungmann admits, “The role of the laity was to all intents and purposes that of a spectator.” One example of this was the lack of congregational participation in the music of worship. He notes disapprovingly that there was “a choir of clerics singing the music belonging to the people!”

Participation in the sacrament of the eucharist changed from partaking of the elements to merely gazing upon them: “Because the faithful no longer wanted to communicate or dared to (the clergy did not encourage frequent reception, to put it mildly), they wanted to see the sacred Host.” This led to the practice of eucharistic veneration and a similar visual fascination with relics of the saints. An increasingly superstitious approach to worship developed which “stressed mere physical presence at Mass in order to gain its fruits.”

In such a state of affairs, Jungmann admits:

It was not hard for Luther to strike a destructive blow against such a system. At least at the outset, he and the other reforming influences already at work in the Church were undoubtedly moved by genuine religious concern. Luther demanded a return to a more simple Christianity.

While the Roman Catholic Jungmann was no apologist for the Protestant cause, he evidenced clear insight into the conditions that spurred the Reformers into action.

John Calvin, for example, made the reformation of worship a top priority. When addressing the question of “by what things chiefly the Christian religion has a standing existence among us,” he answered, “a knowledge, first, of the mode in which God is duly worshipped.” In Geneva, Calvin restored worship to the congregation by conducting services in the language of the people and urging their participation in prayers, praise, and the eucharist. He redressed superstitious practices involving the saints, relics, and theatrical ceremonies. True worship, he reasoned, was to be based on God’s Word and not human whims. Calvin wrote of worship, “We may not adopt any device which seems fit to ourselves, but look to the injunctions of Him who alone is entitled to prescribe.”

The Reformation recovery of Biblical worship and the renewal of proper congregational participation in the liturgy are things worth celebrating. We should not take for granted faithful preaching of Scripture in a language we can understand and the privilege of praying and singing praise to God together each Lord’s Day. These things had once been denied to God’s people, and they are among the many gifts that have come down to us from the Reformation. Let us celebrate this heritage, and, more importantly, live in light of it. Let us enter into worship with hearts and minds fully engaged in honoring God, learning from His Word, and being assured at His sacramental table. When we do so, we will carry on the great legacy of the Reformers. Soli Deo Gloria! To God alone be the glory!

Join us for our Reformation Conference, October 28th – 29th!