Art Matters: In Defense of John Calvin

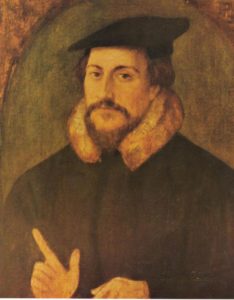

A few years ago I read an engaging essay by Lauren F. Winner entitled, “The Art Patron: Someone Who Can’t Draw a Straight Line Tries to Defend Her Art-Buying Habit.”[1]In it, she offers an apology for Christians spending money on art even when there are other good ways such money could be used. I appreciate what she says and am sympathetic to her perspective. But one thing about the essay grated on me. She writes, “Granted, there is a strain in Christian theology that is hostile to visual art – that says art is a waste of time, or an indulgence, tantamount to idolatry.” I was nodding in concerned agreement as I quickly turned to the endnote to learn what modern fundamentalist scoundrel she cited to justify this statement. I was shocked to find that the note reads in its entirety, “See John Calvin, InstitutesI.xi.” That raised my Presbyterian hackles. Was Calvin really the enemy of the arts that Ms. Winner implies him to have been? The answer is decidedly, “No.”

That chapter in the Institutes of the Christian Religion is entitled, “It Is Unlawful to Attribute a

Visible Form to God, and Generally Whoever Sets Up Idols Revolts Against the True God.” The

entire section is a critique of idolatry, especially of making visible representations of the invisible God to be used in worship. Calvin pulls no punches in condemning such idolatry, but

he also makes clear that he is not thereby condemning artistic creation per se. He writes:

And yet I am not gripped by the superstition of thinking absolutely no images permissible. But because sculpture and painting are gifts of God, I seek a pure and legitimate use of each, lest those things which the Lord has conferred upon us for his glory and our good be not only polluted by perverse misuse but also turned to our destruction.

In the clearest of terms, Calvin declares the visual arts to be “gifts of God” which He has given us “for his glory and our good.” These are hardly the words of one who “says art is a waste of time, or an indulgence, tantamount to idolatry”! Calvin affirms the goodness of art while warning against its abuse.

The fact is that Reformed theology, historically rooted in Calvin, provides fertile soil in which the arts can thrive. Abraham Kuyper noted this in his Stone Lectures at Princeton in 1898:

[I]f we confess that the world once was beautiful, but by the curse has become undone, and by a final catastrophe is to pass to its full state of glory, excelling even the beautiful of paradise, then art has the mystical task of reminding us in its productions of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster. Now this last-mentioned instance is the Calvinistic confession…. Standing by the ruins of this once so wonderfully beautiful creation, art points out to the Calvinist both the still visible lines of the original plan, and what is even more, the splendid restoration by which the Supreme Artist and Master-Builder will one day renew and enhance even the beauty of His original creation.

Kuyper’s statement doesn’t constitute a full-fledged Christian aesthetic, but it does demonstrate how Calvinistic thinking comports with a very positive view of the arts.

Writers of the Calvinian school have been among the most active in modern times in developing and promoting Christian aesthetic concerns in evangelical circles. In this regard, one can cite Reformed scholars such as Hans Rookmaaker (Modern Art and the Death of a Culture), Calvin Seerveld (Rainbows for the Fallen World), and Nicholas Wolterstorff (Art in Action: Towards a Christian Aesthetic). At the popular level, Francis Schaeffer (Art and the Bible) powerfully challenged Christians to have an interest in art and to be supportive of artists. I suspect that, directly or indirectly, Ms. Winner’s appreciation of art as a Christian owes a debt to such heirs of John Calvin.

We certainly want to acknowledge that debt and live up to our heritage when it comes to the arts at Covenant Presbyterian Church. We reject Art (with a capital “A”) as a religion unto itself, but we affirm the arts as an arena in which we can honor God and bless those made in his image.

To that end, our Reformation Conference this year will be dedicated to the theme, “The Reformation and the Arts.” Musician/pastor/author Kemper Crabb will speak about how the Reformation provided liberation for art to flourish. And he will share his own artistic gifts with us through a musical concert on Sunday night. Please plan to join us with our special guest, Kemper Crabb, on Sunday, October 27th.

[1]This appears as chapter 3 in W. David O. Taylor, ed., For the Beauty of the Church: Casting a Vision for the Arts(Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2010).

Kemper Crabb Concert

Covenant Presbyterian Church is pleased to host Kemper Crabb in concert on Sunday, October 27th at 5 PM. The concert is part of our celebration of “The Reformation and the Arts” and is free and open to all.

Kemper has written of his vision as a Christian artist:

All of creation is the Ultimate, Ongoing Work of Art. God is the Ultimate Artist, and we, created in His Image, make Art that, like everything else, reveals God. It is also true that, as Christians called to be artists, we are specifically called to utilize our gift … in such a way that men see God, His Glory, more clearly in Creation, and are thus affected by that vision.

Kemper Crabb has more than four decades of experience as a Christian musician. His first band, Redemption, released an album in 1974 that exemplifies the “Jesus Music” of that era. Redemption evolved to become ArkAngel whose Tolkien-influenced 1980 album, Warrior, is considered a classic by believers and non-believers alike. In 1982, Kemper blended Medieval and Celtic themes on The Vigil.

From the 1990’s on, Kemper has been actively performing and recording. Among a number of releases are two Christmas albums: A Medieval Christmas (1996) and Downe in Yon Forrest (2009). The latter is the soundtrack for his Christmas concert broadcast on PBS. He has performed and recorded with the bands Caedmon’s Call and Atomic Opera. His 2010 album, Reliquarium: Future Hymns from the Ancient World, was produced to honor and raise funds for his father’s missionary work.

A solo performance by Kemper Crabb is a rare treat, and we hope you’ll join us!

Church Address: 3720 N. Highland Ave., Jackson, TN 38305

On the Glory of “Cuttin’ Grass”

I remember entering through the glass doors and immediately seeing Adam. One couldn’t miss his hulking figure dominating the painting — well-lit and obviously meant to be the focal point at the gallery’s entrance. The exhibition entitled, Andrew Wyeth: Close Friends, featured works by Wyeth relating to African-American neighbors in his community of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Adam Johnson, the titular subject of this particular painting, mowed grass and did odd jobs for the Wyeth family over many years. Adam was Wyeth’s last portrait of the man. His fur cap and heavy overcoat over a denim jacket indicate a winter setting. Adam stands in the foreground, looking downward with eyes almost closed, before one of his work sheds. With hands at his sides, perhaps he is walking away from a job just completed. Bob Dylan once sang that dignity has never been photographed, but I think this painting and others in the exhibit show Wyeth rather successful at painting dignity. Or, more accurately, of painting with dignity folks like Adam Johnson who led a hardscrabble existence. Other Wyeth works feature Adam’s house as well as sheds and fences showing signs of his activity — an overturned basket perched on a post, a jacket folded over barbed wire, hay stacked as winter fodder. Adam is thus present in paintings even when his figure is absent. He has touched this landscape, changed it, made it his own.

The exhibition catalog includes a quotation from Adam referencing himself and his painter friend: “Andy — he’s got the glory of painting and I got the glory of cuttin’ grass, and we ain’t gonna get nothing else.” One could take that in a negative sense, as if Johnson laments his lot in life. But would he use the word “glory” to express such a sentiment? I think that Adam, who was said to be deeply religious, saw that there really was glory in “cuttin’ grass,” just as there was glory in painting. There was something good and right and even revelatory about finding one’s calling in creation and pursuing it with gusto.

Ruminating on this painting and quotation sends my mind back to another Adam, the first Adam. Like Adam Johnson, he was a worker — placed in the garden of Eden “to tend and keep it” (Gen. 2.15). This Adam lived in a wonderful, unfallen world, but he was not supposed to leave it as it was. Pristine wilderness was never the divine plan for all of creation. There was latent glory waiting to be developed as Adam explored the world, learned to work with its resources, and put his stamp upon it in God-honoring ways. This was his duty and his privilege. As my Old Testament professor, Meredith Kline, once wrote, “Invited to be a fellow laborer with God — that is the dignity of man the worker and the zest and glory of man’s labor.”

I do not know whether Andrew Wyeth would have thought in such theocentric categories. But as an image-bearer of God with keen artistic vision, he had a richly human understanding of such things that he captured well in his portrayals of Adam Johnson and his world. Many people justly praise the glory of Wyeth’s paintings. But if we view them through his eyes,we just might come to understand something of the glory of cutting grass and of any of the myriad other callings not often celebrated in our society. We might also be led to reflect on the glory of our own callings and to consider the next way we might put our stamp upon our world for the honor of our Creator.