REFORMATION CONFERENCE

Reformation Conference 2022

Sunday, October 30th

Guest Speaker: Dr. Bradley G. Green

Theme: “Faith & Works: A Reformational Perspective”

Sunday Morning:

9:30 AM: Morning Worship Service

Sermon: “Justification and Divine Forbearance” (Ro. 3:21-26)

11:00 AM: Sunday School

“Faith and Works, Part I”

Sunday Afternoon:

12 Noon: Fellowship Meal (Fellowship Hall)

Sunday Evening:

5 PM: Evening Worship Service

“Faith and Works, Part II”

Art Matters: In Defense of John Calvin

A few years ago I read an engaging essay by Lauren F. Winner entitled, “The Art Patron: Someone Who Can’t Draw a Straight Line Tries to Defend Her Art-Buying Habit.”[1]In it, she offers an apology for Christians spending money on art even when there are other good ways such money could be used. I appreciate what she says and am sympathetic to her perspective. But one thing about the essay grated on me. She writes, “Granted, there is a strain in Christian theology that is hostile to visual art – that says art is a waste of time, or an indulgence, tantamount to idolatry.” I was nodding in concerned agreement as I quickly turned to the endnote to learn what modern fundamentalist scoundrel she cited to justify this statement. I was shocked to find that the note reads in its entirety, “See John Calvin, InstitutesI.xi.” That raised my Presbyterian hackles. Was Calvin really the enemy of the arts that Ms. Winner implies him to have been? The answer is decidedly, “No.”

That chapter in the Institutes of the Christian Religion is entitled, “It Is Unlawful to Attribute a

Visible Form to God, and Generally Whoever Sets Up Idols Revolts Against the True God.” The

entire section is a critique of idolatry, especially of making visible representations of the invisible God to be used in worship. Calvin pulls no punches in condemning such idolatry, but

he also makes clear that he is not thereby condemning artistic creation per se. He writes:

And yet I am not gripped by the superstition of thinking absolutely no images permissible. But because sculpture and painting are gifts of God, I seek a pure and legitimate use of each, lest those things which the Lord has conferred upon us for his glory and our good be not only polluted by perverse misuse but also turned to our destruction.

In the clearest of terms, Calvin declares the visual arts to be “gifts of God” which He has given us “for his glory and our good.” These are hardly the words of one who “says art is a waste of time, or an indulgence, tantamount to idolatry”! Calvin affirms the goodness of art while warning against its abuse.

The fact is that Reformed theology, historically rooted in Calvin, provides fertile soil in which the arts can thrive. Abraham Kuyper noted this in his Stone Lectures at Princeton in 1898:

[I]f we confess that the world once was beautiful, but by the curse has become undone, and by a final catastrophe is to pass to its full state of glory, excelling even the beautiful of paradise, then art has the mystical task of reminding us in its productions of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster. Now this last-mentioned instance is the Calvinistic confession…. Standing by the ruins of this once so wonderfully beautiful creation, art points out to the Calvinist both the still visible lines of the original plan, and what is even more, the splendid restoration by which the Supreme Artist and Master-Builder will one day renew and enhance even the beauty of His original creation.

Kuyper’s statement doesn’t constitute a full-fledged Christian aesthetic, but it does demonstrate how Calvinistic thinking comports with a very positive view of the arts.

Writers of the Calvinian school have been among the most active in modern times in developing and promoting Christian aesthetic concerns in evangelical circles. In this regard, one can cite Reformed scholars such as Hans Rookmaaker (Modern Art and the Death of a Culture), Calvin Seerveld (Rainbows for the Fallen World), and Nicholas Wolterstorff (Art in Action: Towards a Christian Aesthetic). At the popular level, Francis Schaeffer (Art and the Bible) powerfully challenged Christians to have an interest in art and to be supportive of artists. I suspect that, directly or indirectly, Ms. Winner’s appreciation of art as a Christian owes a debt to such heirs of John Calvin.

We certainly want to acknowledge that debt and live up to our heritage when it comes to the arts at Covenant Presbyterian Church. We reject Art (with a capital “A”) as a religion unto itself, but we affirm the arts as an arena in which we can honor God and bless those made in his image.

To that end, our Reformation Conference this year will be dedicated to the theme, “The Reformation and the Arts.” Musician/pastor/author Kemper Crabb will speak about how the Reformation provided liberation for art to flourish. And he will share his own artistic gifts with us through a musical concert on Sunday night. Please plan to join us with our special guest, Kemper Crabb, on Sunday, October 27th.

[1]This appears as chapter 3 in W. David O. Taylor, ed., For the Beauty of the Church: Casting a Vision for the Arts(Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2010).

Reformation Conference, Oct. 27-28

Dr. W. Duncan Rankin will be our speaker at this year’s Reformation Conference, focusing on the Scottish Reformation. Read this full post for details and schedule.

Continue readingThe Reformation of Worship

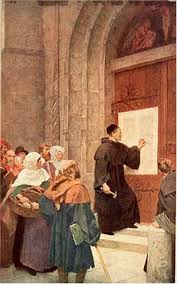

October 31, 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther nailing the “95 Theses” to the door of the church in Wittenberg — a signal event often viewed as launching the Protestant Reformation. Many churches will be commemorating and celebrating this anniversary, but this strikes some as odd. A Roman Catholic friend once asked me how it was that Protestants could celebrate one of the greatest schisms in the history of the Church. I replied that we don’t celebrate separation. The Reformation was a tragic necessity given the condition of the Church at the time. We celebrate the fact that the Reformation was a time of recovery and renewal in doctrine and practice. Nowhere is this more evident than in the matter of worship.

The words of a modern Roman Catholic can help us understand the necessity of the reformation of worship in Luther’s day. Josef A. Jungmann, one of the leading Roman Catholic liturgical scholars of the 20th century, outlined the state of late medieval European piety in a 1959 journal article entitled, “Liturgy on the Eve of the Reformation.” While noting some external signs of vibrant liturgical life (active participation in events of church calendar, multiplication of gothic cathedrals, etc.), he acknowledged many signs of weakness and decline.

One key problem was the shift from worship by the people to worship by and for the clergy: “the liturgy was a liturgy for the clergy … [even] in the churches in which the worship of the faithful should have been the primary concern.” Literal barriers entered the sanctuary, such as the rood screen behind which the clergy conducted the mass. Then there was the language barrier, with the services conducted in Latin that the people could not understand. Jungmann admits, “The role of the laity was to all intents and purposes that of a spectator.” One example of this was the lack of congregational participation in the music of worship. He notes disapprovingly that there was “a choir of clerics singing the music belonging to the people!”

Participation in the sacrament of the eucharist changed from partaking of the elements to merely gazing upon them: “Because the faithful no longer wanted to communicate or dared to (the clergy did not encourage frequent reception, to put it mildly), they wanted to see the sacred Host.” This led to the practice of eucharistic veneration and a similar visual fascination with relics of the saints. An increasingly superstitious approach to worship developed which “stressed mere physical presence at Mass in order to gain its fruits.”

In such a state of affairs, Jungmann admits:

It was not hard for Luther to strike a destructive blow against such a system. At least at the outset, he and the other reforming influences already at work in the Church were undoubtedly moved by genuine religious concern. Luther demanded a return to a more simple Christianity.

While the Roman Catholic Jungmann was no apologist for the Protestant cause, he evidenced clear insight into the conditions that spurred the Reformers into action.

John Calvin, for example, made the reformation of worship a top priority. When addressing the question of “by what things chiefly the Christian religion has a standing existence among us,” he answered, “a knowledge, first, of the mode in which God is duly worshipped.” In Geneva, Calvin restored worship to the congregation by conducting services in the language of the people and urging their participation in prayers, praise, and the eucharist. He redressed superstitious practices involving the saints, relics, and theatrical ceremonies. True worship, he reasoned, was to be based on God’s Word and not human whims. Calvin wrote of worship, “We may not adopt any device which seems fit to ourselves, but look to the injunctions of Him who alone is entitled to prescribe.”

The Reformation recovery of Biblical worship and the renewal of proper congregational participation in the liturgy are things worth celebrating. We should not take for granted faithful preaching of Scripture in a language we can understand and the privilege of praying and singing praise to God together each Lord’s Day. These things had once been denied to God’s people, and they are among the many gifts that have come down to us from the Reformation. Let us celebrate this heritage, and, more importantly, live in light of it. Let us enter into worship with hearts and minds fully engaged in honoring God, learning from His Word, and being assured at His sacramental table. When we do so, we will carry on the great legacy of the Reformers. Soli Deo Gloria! To God alone be the glory!

Join us for our Reformation Conference, October 28th – 29th!