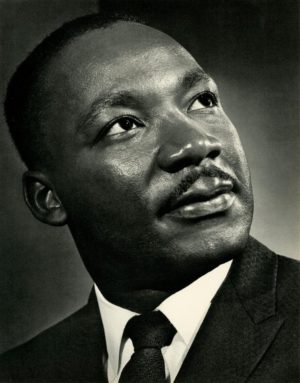

Martin Luther King on the Complete Life

In the summer of 1958, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered two devotional addresses to the first National Conference on Christian Education of the United Church of Christ at Purdue University.[1] I would like to revisit the second address entitled, “The Dimensions of a Complete Life.” In it, Dr. King helpfully provides a balanced view of how we are called to live as followers of Jesus Christ.

He begins by recalling John’s vision of the New Jerusalem descending to earth in Revelation 21. Dr. King notes that the completeness of the city was symbolized the equality of its length, breadth, and height – which make it a perfect cube. From that observation, he proceeds to discuss three “dimensions” of life to which we are all called to attend.

The first dimension is the personal, “in which the individual pursues personal ends and ambitions.” While moving too far in this dimension may lead to narcissism, it is nevertheless appropriate to have a proper self-regard and ambition. Dr. King describes how this should be the case in the vocational aspect of our lives: “No matter how small one thinks his life’s work is in terms of the norms of the world and the so-called big jobs, he must realize that it has cosmic significance if he is serving humanity and doing the will of God.” This is a helpful corrective to false thinking that views some callings as more significant than others in the eyes of God. He provides an effective illustration to make his point:

To carry this to an extreme, if it falls to your lot to be a street-sweeper, sweep streets as Raphael painted pictures, sweep streets as Michelangelo carved marble, sweep streets as Beethoven composed music, sweep streets as Shakespeare wrote poetry. Sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will have to pause and say, “Here lived a great street-sweeper who swept his job well.”

In the personal dimension of life, we are called to be the best that we can be when that is kept in balance with the other dimensions.

The second dimension of life has to do with others. It is absolutely essential that we attend to it: “An individual has not started living until he can rise above the narrow confines of his individualistic concerns to the broader concerns of all humanity.” Dr. King relates Jesus’ parable of the good Samaritan, comparing what thinking might have been behind the responses of the priest and Levite on the one hand and the Samaritan on the other:

I imagine the first question that the priest and the Levite asked was this: “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” Then the good Samaritan came by, and by the very nature of his concern reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” And so this man was great because he had the mental equipment for a dangerous altruism.

Dr. King warns against focusing exclusively on our personal concerns, instead calling us to recognize “that we are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.” Like the Samaritan man in the parable, we must be willing to place the needs of others above our own – at times even engaging in “a dangerous altruism.”

The third dimension has to do with our relationship with God. Dr. King observes that some people master the first two dimensions without ever getting around to the third. When they do this, “They find themselves bogged down on the horizontal plane without being integrated on the vertical plane.” No life is complete that leaves God out of the picture. And yet, he notes that it is easy to forget this in our modern world:

We so often find ourselves neglecting this third dimension of life. Not that we go up and say, “Good-by, God, we are going to leave you now.” But we become so involved in the things of this world that we are unconsciously carried away by the rushing tide of materialism which leaves us treading in the confused waters of secularism.

How that description rings true to the temptation that comes to those of us ensconced in the middle class American lifestyle! When our basic personal needs seem always to be provided, we often have little thought for God. But, as Dr. King writes, “Without him, life is a meaningless drama with the decisive scenes missing.” Hence, he issues a call for all to seek and to nurture a relationship with God.

Not only is this presentation helpful in terms of it personal application in our lives; it is also salutary when we look back and evaluate the life and work of Dr. King himself. Because of his leadership in the Civil Rights movement, it might be thought that his attention was focused exclusively on the second dimension – raising the life conditions of others who were being mistreated as victims of racial prejudice. But he was also interested in the first dimension, challenging every individual to embrace his or her calling with a larger vision in mind. And the third dimension was absolutely essential to this ordained minister. The ultimate goal for all people involved not just horizontal equality but vertical reconciliation. No life could be complete without a right relationship with God.

Consider, in closing, Dr. King’s summary of his vision of the three dimensions of the complete life:

Love yourself, if that means rational, healthy, and moral self-interest. You are commanded to do that. That is the length of life. Love your neighbor as you love yourself. You are commanded to do that. That is the breadth of life. But never forget that there is a first and even greater commandment, “Love the Lord thy God with all thy heart and all thy soul and all thy mind.” This is the height of life. And when you do this you live the complete life.

[1]All quotations are from the published version of these two addresses: Martin Luther King, Jr., The Measure of a Man(Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 2013).

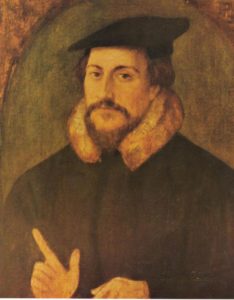

Art Matters: In Defense of John Calvin

A few years ago I read an engaging essay by Lauren F. Winner entitled, “The Art Patron: Someone Who Can’t Draw a Straight Line Tries to Defend Her Art-Buying Habit.”[1]In it, she offers an apology for Christians spending money on art even when there are other good ways such money could be used. I appreciate what she says and am sympathetic to her perspective. But one thing about the essay grated on me. She writes, “Granted, there is a strain in Christian theology that is hostile to visual art – that says art is a waste of time, or an indulgence, tantamount to idolatry.” I was nodding in concerned agreement as I quickly turned to the endnote to learn what modern fundamentalist scoundrel she cited to justify this statement. I was shocked to find that the note reads in its entirety, “See John Calvin, InstitutesI.xi.” That raised my Presbyterian hackles. Was Calvin really the enemy of the arts that Ms. Winner implies him to have been? The answer is decidedly, “No.”

That chapter in the Institutes of the Christian Religion is entitled, “It Is Unlawful to Attribute a

Visible Form to God, and Generally Whoever Sets Up Idols Revolts Against the True God.” The

entire section is a critique of idolatry, especially of making visible representations of the invisible God to be used in worship. Calvin pulls no punches in condemning such idolatry, but

he also makes clear that he is not thereby condemning artistic creation per se. He writes:

And yet I am not gripped by the superstition of thinking absolutely no images permissible. But because sculpture and painting are gifts of God, I seek a pure and legitimate use of each, lest those things which the Lord has conferred upon us for his glory and our good be not only polluted by perverse misuse but also turned to our destruction.

In the clearest of terms, Calvin declares the visual arts to be “gifts of God” which He has given us “for his glory and our good.” These are hardly the words of one who “says art is a waste of time, or an indulgence, tantamount to idolatry”! Calvin affirms the goodness of art while warning against its abuse.

The fact is that Reformed theology, historically rooted in Calvin, provides fertile soil in which the arts can thrive. Abraham Kuyper noted this in his Stone Lectures at Princeton in 1898:

[I]f we confess that the world once was beautiful, but by the curse has become undone, and by a final catastrophe is to pass to its full state of glory, excelling even the beautiful of paradise, then art has the mystical task of reminding us in its productions of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster. Now this last-mentioned instance is the Calvinistic confession…. Standing by the ruins of this once so wonderfully beautiful creation, art points out to the Calvinist both the still visible lines of the original plan, and what is even more, the splendid restoration by which the Supreme Artist and Master-Builder will one day renew and enhance even the beauty of His original creation.

Kuyper’s statement doesn’t constitute a full-fledged Christian aesthetic, but it does demonstrate how Calvinistic thinking comports with a very positive view of the arts.

Writers of the Calvinian school have been among the most active in modern times in developing and promoting Christian aesthetic concerns in evangelical circles. In this regard, one can cite Reformed scholars such as Hans Rookmaaker (Modern Art and the Death of a Culture), Calvin Seerveld (Rainbows for the Fallen World), and Nicholas Wolterstorff (Art in Action: Towards a Christian Aesthetic). At the popular level, Francis Schaeffer (Art and the Bible) powerfully challenged Christians to have an interest in art and to be supportive of artists. I suspect that, directly or indirectly, Ms. Winner’s appreciation of art as a Christian owes a debt to such heirs of John Calvin.

We certainly want to acknowledge that debt and live up to our heritage when it comes to the arts at Covenant Presbyterian Church. We reject Art (with a capital “A”) as a religion unto itself, but we affirm the arts as an arena in which we can honor God and bless those made in his image.

To that end, our Reformation Conference this year will be dedicated to the theme, “The Reformation and the Arts.” Musician/pastor/author Kemper Crabb will speak about how the Reformation provided liberation for art to flourish. And he will share his own artistic gifts with us through a musical concert on Sunday night. Please plan to join us with our special guest, Kemper Crabb, on Sunday, October 27th.

[1]This appears as chapter 3 in W. David O. Taylor, ed., For the Beauty of the Church: Casting a Vision for the Arts(Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2010).

A Time for Tears

“Rivers of water run down from my eyes, because men do not keep Your law.” (Psalm 119.136)

It is not hard to discern that we live in an age of shaky moral standards. From entertainment to advertising to news stories, we are confronted with images and messages that challenge Biblical morality. The murder of unborn babies is justified in the name of choice. Immigrants are vilified in the name of patriotism. Sexual mores have been cast aside in the name of personal freedom. Greed and oppression are justified in the name of capitalism. How are we as Christians to respond when people around us reject the principles of God’s law?

One possible response is to rally the troops so we can loudly and publicly denounce all that we perceive to be ungodly. We can take to the streets with slogans on banners and fists in the air. There is no doubt that this approach yields results. The media love to focus their cameras on the faces of angry Christians and to thrust their microphones before those who are ranting and raving. The louder and loonier you are, the easier it is to get attention. Yet, is this what God would have us do?

The psalmist points us in a different direction with the testimony, “Rivers of water run down from my eyes, because men do not keep Your law.” Why was weeping his response to the law-breaking of others? Why was he not satisfied simply to keep the law himself? The answer is that he was filled with a profound love for God and neighbor, which is what Jesus said the law was all about (Matthew 22.37-40).

If you really love someone, you take offense when others treat him with dishonor. God is the great lawgiver, and His law is an expression of His character of holiness, justice, righteousness, and love. When men and women ignore that law, they are thumbing their noses at the Lawgiver (whether they realize it or not). The psalmist’s love for God causes him to grieve when others don’t give God the honor He is due.

If you really love someone, you also want the best for her. God is our Creator, who knows what is best for us and has revealed that in His revelation in Scripture. When our neighbor is defying God’s law, she is missing out on the blessings that God has in store for her. The psalmist’s love for neighbor causes him to weep when others aren’t experiencing the benefits that attend obedience to their Creator.

We can learn some important lessons from the author of Psalm 119. The next time someone who is defying God’s law gets your attention, ask yourself a few questions before you respond. Is my primary concern in this situation the honor of God? Will my response be motivated by genuine love for the one with whom I disagree? I fear that if we were honest, we’d have to say that the answers to these questions would oftentimes be “No.” It is all too easy to act out of self-interest that is perceived (often justly) as self-righteousness. We can be consumed with concern for our own honor (not God’s) and love for self (not neighbor).

This is not to say that it is never appropriate to take a public stand on moral issues of the day. Love can require this! But how we express ourselves is all-important. We should always and only do so with weeping. That may or may not involve literal tears, but that image should express the disposition of hearts driven by genuine love for God and others. It may not put us in the headlines, but we are far more likely to have a positive moral impact in society if we lead with love and not anger. If we never take time for tears, then the most productive thing we can probably do is remain silent and pray that God would soften our hearts.

Witness of the Heavens

The heavens declare the glory of God;

And the firmament shows His handiwork. (Psalm 19.1; NKJV)

Oh, give thanks to the Lord, for He is good!

For His mercy endures forever.

To Him who made the great lights,

For His mercy endures forever –

The sun to rule by day,

For His mercy endures forever;

The moon and stars to rule by night,

For His mercy endures forever. (Psalm 136.1,7-9; NKJV)

Since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead. (Romans 1.20; NKJV)

Scripture teaches that creation constantly bears witness to its Creator. We know that unbelievers suppress this knowledge in an effort to resist God’s claims upon them (Romans 1.18). However, are we believers not often guilty of taking for granted the wonders of creation and failing to appreciate the revelation of God all around us?

I know this is the case for me. That is why I found it remarkable to be caught up short this past weekend beholding the rising moon. I wrote the poem below, which I share as my own testimony and as an encouragement for all of us to be more attentive to the witness of creation.

On Our Evening Walk

Rounding the corner, she stopped

and dropped my hand to point

and to declare:

“Look! The moon!”

I saw it rising between the rooftops –

full, glowing, seemingly-swollen

to three times its normal size.

We gazed in wonder,

caught up in this unexpected glimpse of glory.

Walking on, we called first to a neighbor

and then to our children,

“Look! The moon!”

And, together, we marveled.

(12/2/17)

© 2017, Steven C. Wright

On the Glory of “Cuttin’ Grass”

I remember entering through the glass doors and immediately seeing Adam. One couldn’t miss his hulking figure dominating the painting — well-lit and obviously meant to be the focal point at the gallery’s entrance. The exhibition entitled, Andrew Wyeth: Close Friends, featured works by Wyeth relating to African-American neighbors in his community of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. Adam Johnson, the titular subject of this particular painting, mowed grass and did odd jobs for the Wyeth family over many years. Adam was Wyeth’s last portrait of the man. His fur cap and heavy overcoat over a denim jacket indicate a winter setting. Adam stands in the foreground, looking downward with eyes almost closed, before one of his work sheds. With hands at his sides, perhaps he is walking away from a job just completed. Bob Dylan once sang that dignity has never been photographed, but I think this painting and others in the exhibit show Wyeth rather successful at painting dignity. Or, more accurately, of painting with dignity folks like Adam Johnson who led a hardscrabble existence. Other Wyeth works feature Adam’s house as well as sheds and fences showing signs of his activity — an overturned basket perched on a post, a jacket folded over barbed wire, hay stacked as winter fodder. Adam is thus present in paintings even when his figure is absent. He has touched this landscape, changed it, made it his own.

The exhibition catalog includes a quotation from Adam referencing himself and his painter friend: “Andy — he’s got the glory of painting and I got the glory of cuttin’ grass, and we ain’t gonna get nothing else.” One could take that in a negative sense, as if Johnson laments his lot in life. But would he use the word “glory” to express such a sentiment? I think that Adam, who was said to be deeply religious, saw that there really was glory in “cuttin’ grass,” just as there was glory in painting. There was something good and right and even revelatory about finding one’s calling in creation and pursuing it with gusto.

Ruminating on this painting and quotation sends my mind back to another Adam, the first Adam. Like Adam Johnson, he was a worker — placed in the garden of Eden “to tend and keep it” (Gen. 2.15). This Adam lived in a wonderful, unfallen world, but he was not supposed to leave it as it was. Pristine wilderness was never the divine plan for all of creation. There was latent glory waiting to be developed as Adam explored the world, learned to work with its resources, and put his stamp upon it in God-honoring ways. This was his duty and his privilege. As my Old Testament professor, Meredith Kline, once wrote, “Invited to be a fellow laborer with God — that is the dignity of man the worker and the zest and glory of man’s labor.”

I do not know whether Andrew Wyeth would have thought in such theocentric categories. But as an image-bearer of God with keen artistic vision, he had a richly human understanding of such things that he captured well in his portrayals of Adam Johnson and his world. Many people justly praise the glory of Wyeth’s paintings. But if we view them through his eyes,we just might come to understand something of the glory of cutting grass and of any of the myriad other callings not often celebrated in our society. We might also be led to reflect on the glory of our own callings and to consider the next way we might put our stamp upon our world for the honor of our Creator.